Last week, I visited Pergamon Museum and Neues Museum, two of five museums in Museuminsel, Berlin. Using my student card, the 3-days Museum Pass, valid for 70 museums in the city, only cost me 9.5 euro, the best bargain for museum lovers. Two things came across my mind upon exploring the huge museums: that the Germans love to build massive structures, and that the properties right of the antiquities remains an unanswered question.

The first museum houses at least three gargantuan-sized collections: Pergamon altar, Ishtar gate, and Mshatta facade. Pergamon museum, the newest amongst the five, was built in 1910-1930 to incorporate the giant artefacts, as well as to prove Germany is as great as the British (with their British Museum) and the French (with their Louvre) in terms of collecting — or perhaps more precisely: looting — antiquities.

Pergamon altar, excavated from present-day Turkey, was built in the 2nd century BC. The frieze depicting the battle between the Gods and Giants is regarded as a masterpiece of Hellenistic art. It is 35.64 meters wide and 33.4 meters deep; the front stairway alone is almost 20 meters wide. A German engineer, Carl Humann, began official excavations in 1878, which lasted until 1886. The frieze, along with other collections, was then transported to Germany, put into the museum where the reconstruction is then built (the upper part of the altar is just a reconstruction).

In the collection captions in the museum, the Germans claimed that they legally acquired the friezes along with other collections from the Turkish government, but it is contested by the current government, which demands the artefacts to be returned. Interestingly, some captions in the temporary exhibitions on Pergamon excavation are written not only in German and English, but also in Turkish.

The Ishtar gate, built in 604-562 BC, was situated in the northern city wall of Babylon. It is decorated with lapis lazuli tiles and bas-reliefs of bulls and dragons. The ground plan and the debris of the gate buildings were uncovered during the German excavation at Babylon in 1899-1917, led by Robert Koldewey. In the museum only the first smaller gate, 15 meter high, was reconstructed. The animal reliefs and lower ornament are a composite from the original brick fragments.

Mshatta facade is a part of the 8th century Umayyad residential palace of Qasr Mshatta, one of the Desert Castles in Jordan. The remains of the palace were excavated and discovered in 1840, then the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II gave the facade as a gift to Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany (whether the Jordanians are insulted or not with this gift-giving, I have no idea). It was reconstructed as a 33 metres long, 5 metres high facade, with two towers, and parts of a central gateway. It was seriously damaged during the Second World War and the bombardment of Berlin.

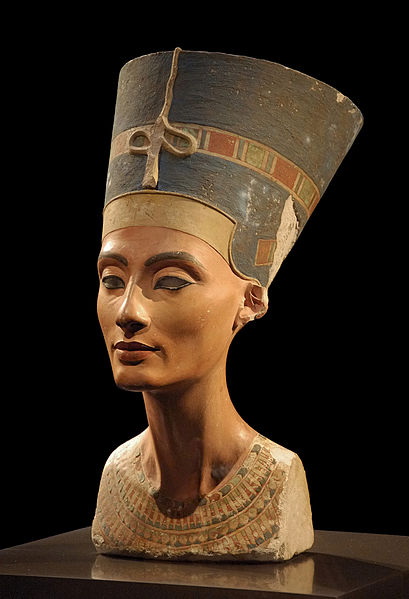

Meanwhile, the Neues Museum houses Egyptian artefacts, Heinrich Schliemann‘s Trojan antiquities, as well as artifacts from the Stone Age and later prehistoric eras. The star attraction is the Nefertiti bust from around 1340 BC, which is shown in its own beautiful room in one corner of the museum. The Egyptian government also demand the return of the queen’s statue, accusing that permission to export it was obtained by deception. Too bad no photography is allowed in that room, so here’s a glimpse of her, taken by Philip Pikart:

The Trojan antiquities were also interesting, showing how the amateur archaeologist strived hard to prove that Troy is not only a mythical place, but exists in reality. Among others, there is this diadem (headdress) which made me wonder how I would look if I wear them, hahaha.

However, the most astonishing part for me is this caption in the Schliemann’s Trojan antiquities section:

See the irony? They claimed the Turks have no right upon the Pergamon altar, but they’re whining about “their” lost Trojan treasure. Anyway, it leads us to the controversy of artefacts (and colonial legacy and the worship of free market): who really own them? Would you rather see the artefacts in some foreign countries or in their home countries? What if the home countries can not maintain or preserve the artefacts?

And I can’t help to wonder where Indonesian artefacts are now — bought, smuggled, traded, auctioned, and scattered around the world.

Leave a Reply